Art & Culture

Sculpted from sugar: Silvertown legend Henry Tate gets a fitting tribute

Deep-fried paintings. Sculptures made of sugar. There’s something about Gala Bell’s art that seems a little, well, tempting. Has she ever wanted to take a nibble out of one of them?

“I haven't nibbled any of them myself,” she says, “but I once had a girl and some of her friends come up to [the sugar towers] during one of the Silvertown parties. They were so amazed that they started licking them from floor to top. It was one of the best moments of my life, to be honest.”

The Hidden 66

Bell's sugar towers have previously gone on display at the London Festival of Architecture.

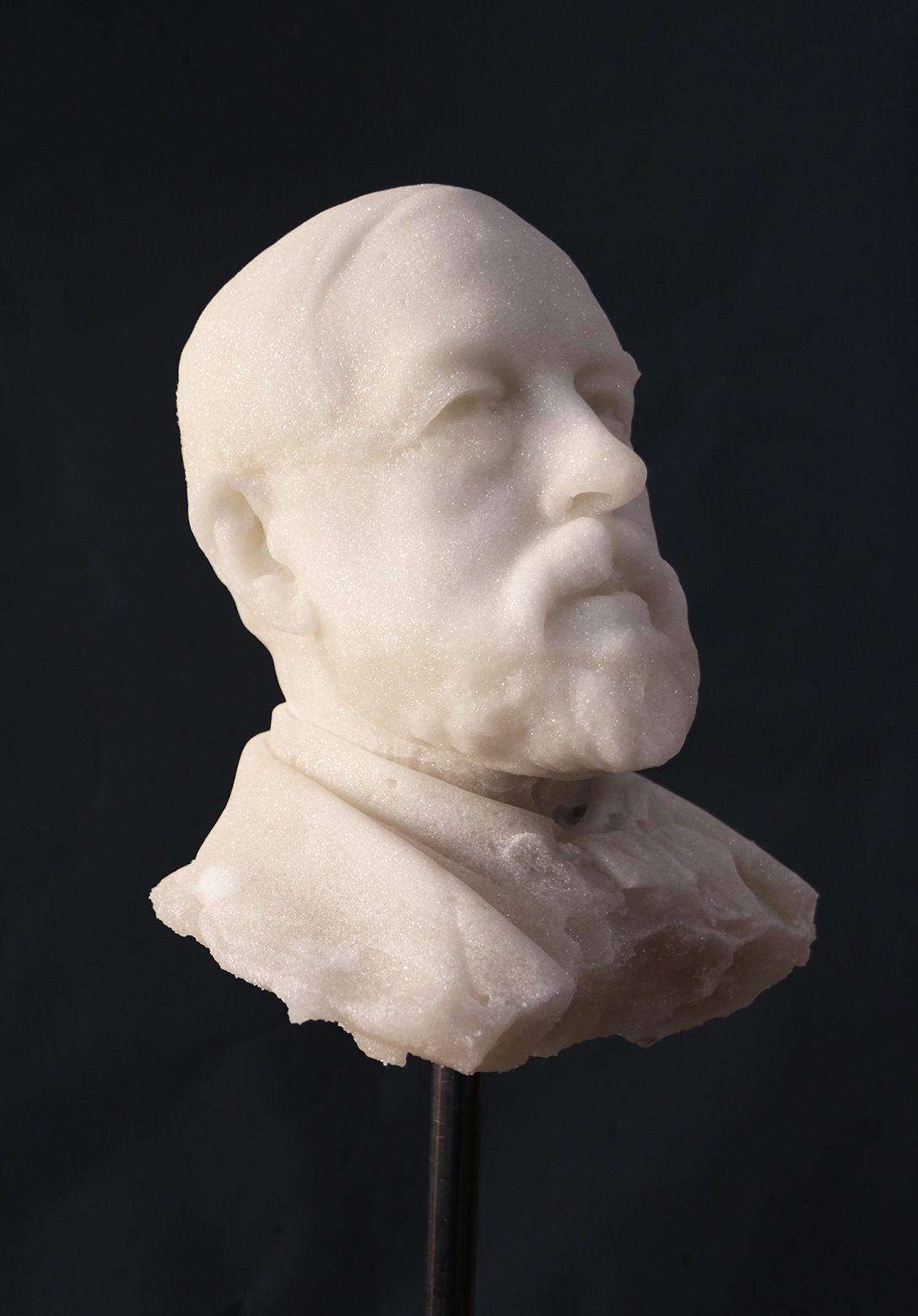

Bell’s here to talk about another of her sugar sculptures: a cast of Henry Tate, the Victorian magnate who founded Tate & Lyle and established the Tate gallery with his fortune and personal art collection. Based out of a studio in the Silver Building, she collaborated with the refinery to produce a sticky monument to their founder. The work appears in a segment for The One Show (from the 25-minute mark) celebrating the 200-year anniversary of Tate's birth.

Bell took a cast of the refinery’s marble bust of Tate, then re-created the sculpture in sugar. As anyone who’s tried to make toffee will know, working with sugar is challenging. “It's a nightmare. You can't predict how much it's going to ooze. I had a 70kg piece at London Design Festival, and the gallery was going nuts because it was constantly leaking.”

So why create art that could ruin the carpet? A nice painting is easier to hang in the living room, but for Bell the effort her works take to look after — even the disgust they can evoke — is the whole point. They force the audience to rethink their relationship with everyday objects, objects that consumer culture makes it easy to ignore or forget about.

Gala Bell at work

Left: preparing the original marble bust of Tate. Right: the cast ready to be filled with sugar.

She describes the moment she took her Sir Henry Tate piece out of its cast, “He was wet from the syrup and it looked as if he'd just come out of the womb. The cast was rounded like a belly, the silicone inside looked like flesh, and there was syrup coming out. It felt like he had been reborn.”

With unnerving smells and sensations, her pieces are more like performances than objects of appreciation. She explains, “I enjoy seeing people's gut reactions to my work. The deep-fried paintings were never aesthetically pleasing. People want to get away from them even if they are intrigued at the same time.” That’s why drunk partygoers licking her sculptures in a frenzy of amazement was exactly the response Bell was hoping for.

Sir Henry, meet Sir Henry

The final sugar sculpture (left), alongside its original. Photo at right: Sam Bush.

One of Bell's long-term ambitions is to deep-fry a bicycle. But when I mention it, she sighs. “It was actually incredibly stressful trying to get a bike deep-fried,” she explains. Even a child’s BMX would need to be immersed in 400-700 litres of oil. Such a quantity could only be heated over an open flame, meaning the attempt would be fraught with danger.

She has spent a good part of this year obsessively pursuing the project. She learned to weld, made a metal tank, and consulted mathematicians and lab technicians at Imperial College. She also talked about it to everyone who would listen: cab drivers, baristas, anyone who crossed her path. Her dream of a deep-fried bike is stalled at the moment as no fire safety officer will sign off on it. Instead, Bell has dozens of recordings of people’s reactions to the idea. Perhaps, she wonders, this archive is what the project has become. “I'm still trying to figure out what the deep-fried bike is really a symbol of.”

Fry Up

Deep-fried painting made of tempura

Getting more significant sponsorship on board might be the key to completing it one day. In the meantime, it’s led to some interesting encounters. “This is a reason that I love Silvertown, because when I first moved in, I had the bike outside my studio, and somebody walked past and said, ‘What are you going to do with that bike?’ ‘Actually, I'm trying to deep fry it.’ And he said, ‘That's a coincidence because I've won the Guinness world record for deep-frying the biggest samosa in the world.’” (Giant samosas: now there’s a story that deserves to be on the Royal Docks website some day.)

Bell arrived in the Silver Building a year ago, when the now-thriving space was still semi-derelict, with only four or five tenants. “The whole area was a playground. It felt like a lost city.” She compares the neighbourhood to the spaceship in the film Solaris (1972): “I felt like it was a different planet. Sometimes I would even drive there, just escape out of London. Honestly, time is slower there.” She’d spend whole afternoons playing with a bow and arrows in the car park — part art installation, part killing time.

Now that the Silver Building is filled with other creative businesses, Bell felt it was time to move on. The meanwhile space is doing something amazing, she explains, but it’s no longer the kind of place that invites you to waste an afternoon messing around in the car park. “I'm sad about it because the light there is incredible.”

Catch the Silver Building’s wonderful light and enchanting events here or follow Gala Bell’s work on her website.