Heritage and history

A history of the Royal Docks

The Royal Docks once drew people and produce into the capital from all over the world. As the docks become a hive of activity once more, here’s a look at the rise, fall, and subsequent resurgence of the city’s industrial heartland.

Early 1800s

Chaos on the river

The British Empire was expanding. Steam power had arrived, and all this meant more trade. It also meant pandemonium on the river. Collisions were frequent and plundering was rife. The Port of London was in chaos and there was a desperate need for more docks with wider and deeper shores. First to be built were the East and West India Docks, which helped relieve the pressure on cargo berths for a while. But it was not enough. The growing city needed a radical solution.

It was then that a group of entrepreneurs, spearheaded by George Parker Bidder, hatched an incredibly ambitious plan: to build docks that were bigger and deeper than anything that had gone before and that could ensure the city of London would be supplied for a century or more. What’s more, their plan was to dig these docks out of the marshland further to the east, in what was to become an incredible feat of engineering.

It’s hard to imagine quite how many men and machines were required to undertake such a task in the early part of the 19th century. But the project was delivered on time and, in 1855, Victoria Dock was opened. Some 13 metres deep and serviced by a giant ship lock, the dock featured the latest technology in dockside cranes and services and, more importantly, could handle multiple numbers of the new iron-clad steamships that were travelling the empire.

At the same time, the demand for land for factories had also exploded. The first of these arrived in 1852: Samuel Silver’s waterproof clothing works, which gave its name to the Silvertown district. By the 1880s, the docks were one of London’s biggest bases for the cargo industry.

King George V Dock

Construction work in progress. Photo: Museum of London.

It’s hard to imagine quite how many men and machines were required to undertake such a task in the early part of the 19th century.

Apples from New Zealand

Cargo being unloaded in 1949. Photo: Newham Archives and Local Studies

1880-1920

A thriving hub for trade

No sooner was Victoria Dock opened than it became clear that more wharf space was required and plans for another dock were developed. Longer than Victoria Dock, these new docks would feature some unique innovations, such as railway lines that went straight to the dock edge, and refrigerated warehousing to store perishable goods. Even electric lighting would follow. Named Albert Dock, this new addition opened in 1880.

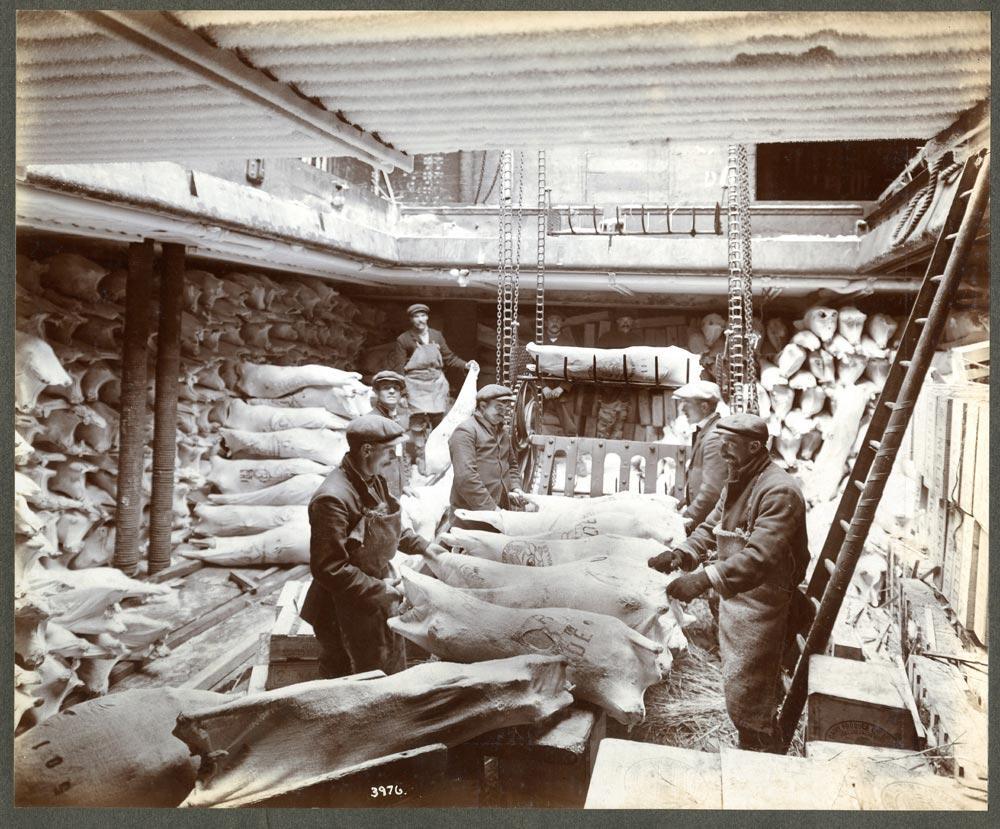

Now linked to the new and expanding railway network, and capable of accommodating the largest iron and steam ships, Victoria and Albert became London’s main docks. Hundreds of thousands of cargoes of grain, tobacco, meat, fruit, and vegetables were unloaded onto the quayside and stored in the giant granaries and refrigerated warehouses. The docks were key to feeding and fuelling Britain in its heyday as a global superpower, importing from colonies such as India, Australia, and New Zealand. Passenger ships also arrived in their hundreds.

As a result, employment opportunities increased, creating a huge demand for accommodation for workers; new settlements originated, known as Hallsville, Canning Town, and North Woolwich. There was also an expansion of housing in areas later known as Custom House, Silvertown, and West Silvertown.

The hazardous nature of work on the docks became notorious on 19 January 1917, when 50 tons of TNT blew up while workers were making munitions at Brunner Mond & Co in Silvertown. 73 people were killed, and up to 70,000 buildings were damaged. The Silvertown Explosion remains the biggest in London’s history.

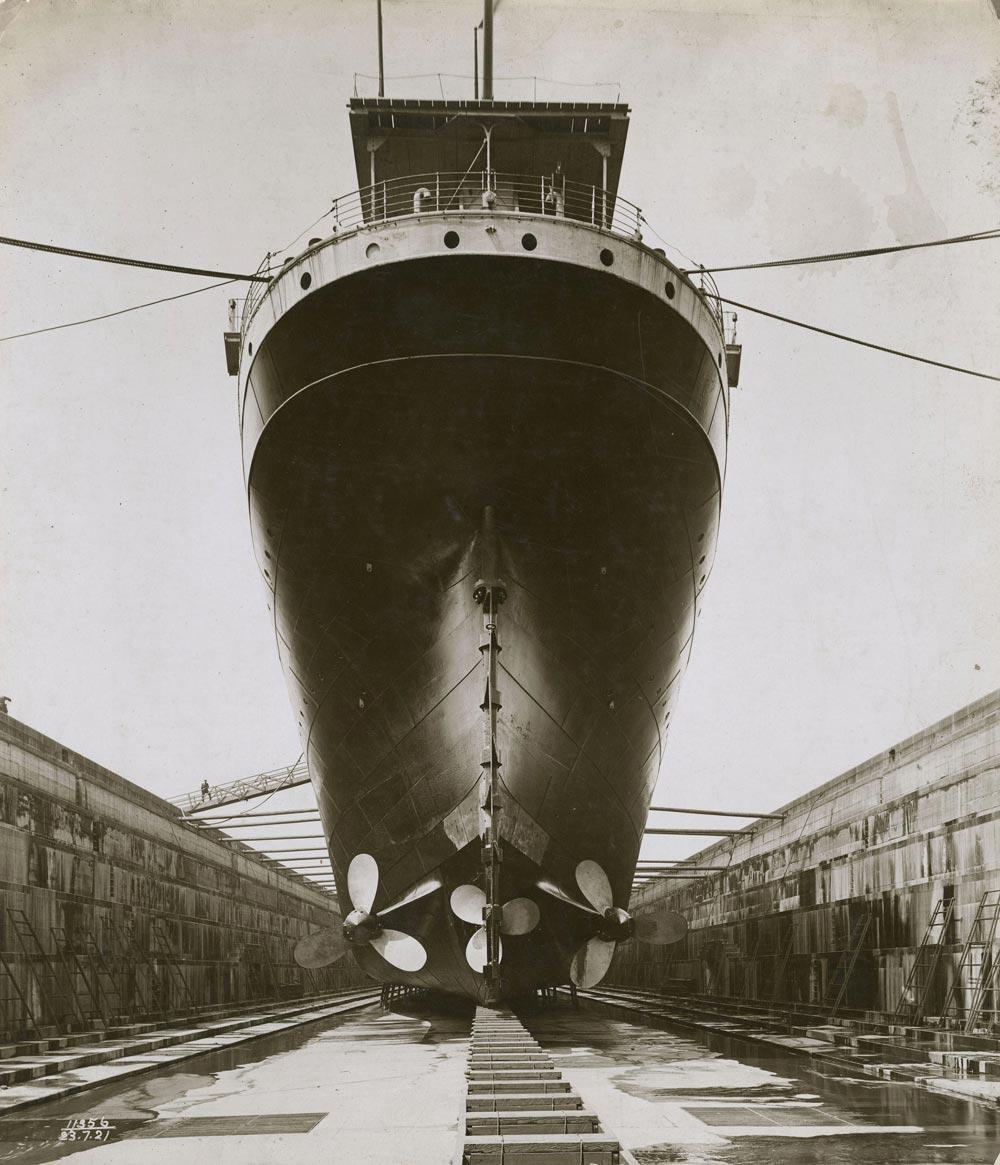

1921

King George V and the ‘Royal’ Docks

The final dock to be constructed was opened by King George V in 1921, with the group of docks being assigned the ‘Royal’ name. King George V Dock featured a new 225 metre-long lock with an entrance big enough to accommodate the 35,655-ton ocean liner the RMS Mauretania in 1939.

1926

The general strike brings work to a standstill

The poor working and living conditions of dockworkers came to a head when a strike was called by the TUC to begin at one minute to midnight on 3 May 1926. It may have only lasted nine days, but this strike hit the Royal Docks hard.

With 750,000 frozen carcasses stored in the warehouse fridges and no electricity supply, the threatened losses were phenomenal. In the nick of time, the Royal Navy came to the rescue with two submarine generators. Although on this occasion this dispute was resolved, continued poor working conditions for dockworkers dogged the Royal Docks and industrial disputes became a feature throughout the remainder of their operation.

With 750,000 frozen carcasses stored in the warehouse fridges and no electricity supply, the threatened losses were phenomenal.

SS Euripides in King George V dry dock

SS Euripides was the first ship to use King George V dry dock, opened on July 23, 1921. It could be flooded with water in one and a half hours. Photo: Museum of London

1939-1945

World War II, The Blitz, and the Normandy landings

The Royal Docks suffered severe damage during World War II. German leaders believed that destroying the port with its warehouses, transit sheds, factories, and utilities would disrupt Britain’s war effort. It is estimated that some 25,000 tons of ordnance fell on the docklands, with much of that on the Royal Docks and surrounding area. Human losses were extremely high, but in spite of the sustained bombardment, the Royal Docks remained open. They handled less shipping due to attacks by German submarines on British merchant ships, which led to food shortages and rationing, but many did get through and the docks helped keep Britain supplied with food.

Towards the end of the war, the Royal Docks played a vital role when the portable harbours for the Normandy landings were constructed in secret within the docks themselves. Once completed, they were towed towards Folkestone and put in place to support the landings and the Allied forces’ push across northern France. Despite the damage, the Royal Docks enjoyed a brief boom in trade after the war and for a while it looked as though the docks would continue to thrive through to the end of the 20th century. But it was not to be.

The Blitz in East London

A German Luftwaffe Heinkel He 111 bomber flying over Wapping and the Isle of Dogs.

1960-1981

The decline and closure of the docklands

The final challenge that the Royal Docks could not sustain came with the creation of containerised cargo, and other technological changes. This far more efficient method of moving goods required much larger ships that could not navigate down as far as the Royal Docks. Large container ports were developed further down the river and gradually the Royal Docks’ business fell into decline. As the docks declined, the Docklands Joint Committee was established, which published the London Docklands Strategic Plan in April 1976. Due to problems with the land and funding, it wasn’t as successful as hoped. However, it had a positive impact in Beckton, confirming its development as a residential area, draining the marshes, and putting in a foul drainage system. Despite the difficulties, the Royals survived longer than any other upstream docks, before finally closing to commercial traffic in 1981. The last vessel to be loaded left on 7 December 1981.

The closure of docks in London led to massive unemployment and social problems across East London.

For a while it looked as though the docks would continue to thrive through to the end of the 20th century.

Mutton in a ship's hold

Photo: Museum of London

Games in the street

This is a family photo from the collection of Silvertown resident Brian Cook.

1981

A new beginning

In mid 1981, the London Docklands Development Corporation was formed with the objective of regenerating and finding new uses for the former docks of London. The DLR was built to revive neglected neighbourhoods, opening in 1987 with just 15 stations. Its first route, connecting Island Gardens with Tower Gateway and Stratford, helped transform once-isolated Canary Wharf into a new financial centre. The lightweight rail system adopted disused viaducts and built new ones, extending out to Beckton by 1994 – an area that had been without any form of train service.

For the Royal Docks themselves, plans were made to create an inner-city airport utilising the former central wharf as the runway. London City Airport opened in 1987 and has been a thriving and convenient departure point for passengers ever since. Later, over on Royal Albert Dock, the University of East London (UEL) opened its largest campus in 1999. Renowned for its sports offer and facilities, it is also one of the few London universities to provide on-campus accommodation. Shortly afterwards, a major exhibition centre was opened, ExCeL London. The venue now hosts 4 million people a year.

The DLR helped transform once-isolated Canary Wharf into a new financial centre.

While the London Docklands Development Corporation was responsible for many of the successes above, it was also opposed by local councils and residents for its lack of consultation. Together, they created an alternative vision for the area, The People’s Plan for the Royal Docks.

Near Royal Victoria, architects Rogers Stirk Harbour & Partners gave a touch of flair to a necessary piece of infrastructure. They described the Tidal Basin Pumping Station, which opened in 1988, as “a visual delight, an oasis in the drab industrial environment of Silvertown” and its bold blue cylinders can be seen today from Seagull Lane.

Such accusations of drabness were not to last long. Thames Barrier Park was installed on what was once one of the river bank’s most polluted former industrial sites. After years of painstaking decontamination, the gardens opened in 2000 as the capital’s largest new riverside park for over 50 years, and has now been recognised with a Green Flag Award. The award-winning design includes a striking sunken garden harking back to the docks’ shipping heritage.

Greenwich Peninsula from the Royal Docks

Photo: Tian Khee Siong

2012

Success under the Olympic spotlight

By 2010, the ExCeL centre had expanded, increasing its footprint by almost 50%. The venue played a key role in the 2012 Olympic Games, hosting seven olympic events as well as paralympics. On the other side of the docks, UEL’s newly opened SportsDock served as a training centre for Team USA during the games. The state-of-the-art sports facility provides pitches, courts, and gyms for students and the public alike.

The DLR was also crucial to the Games’ success, carrying double its normal load of passengers and nudging the network over the 100 million passenger mark for that year. At its peak, numbers using the railway reached 500,000 on a single day.

Also opening that year, a month before the Games began, was the Emirates Air Line. Linking Royal Victoria Dock with North Greenwich, this cable car gives visitors spectacular views over the docks’ waterscape. Meanwhile, The Crystal building made history by becoming the only building in the world to achieve the highest certification in both the BREEAM and LEED sustainability schemes. The Siemens-sponsored venture was home to the world’s largest exhibition on the future of cities.

New Beckton Park

Photo: Sam Bush

2019 and beyond

Today, the Royal Docks is London’s only Enterprise Zone – special areas of opportunity where business rates are reinvested back into the area to support economic growth. Total investment here is likely to reach more than £8bn by 2038. A joint team established by the Mayor of London and Mayor of Newham provides a rare opportunity to champion good growth and ensure transformation that delivers genuine benefits locally.

Residential, commercial, and retail developments are springing up along the four kilometres of the Royal Docks, from Gallions Reach to Royal Victoria. UEL and London City Airport continue to thrive, whilst ExCeL now offers London’s only International Conference Centre. New hotels, restaurants, and coffee shops have opened up, catering to the growing number of people who live, work and study here, as well as increasing numbers of visitors.

Crossrail will bring the Royal Docks into Central London for the first time, connecting Custom House with Liverpool Street in just 10 minutes. To the east, phase one of Royal Albert Dock will also come online. This ambitious development will be a new commercial heart for London, while also welcoming leisure visitors into its pleasing town squares, restaurants, and dockside cafes.

The growth story of the Royal Docks continues. Find out more here about the plans that will ensure the place flourishes in the future.