Forgotten Stories

The silk that fell from the sky

Amid the horrors of war, there are also always tales of remarkable escapes. No contemporary documents record the following incident, which happened one night during World War II. It would have been forever shrouded in wartime secrecy were it not for the memories of one of North Woolwich’s oldest residents. Joan Plant told the story to local journalist and historian Colin Grainger.

The Blitz brings many memories to different generations in the Royal Docks area. Even today, unexploded bombs are still being recovered as new communities are created. Today we can record the remarkable tale of an uninvited guest dropped by the Luftwaffe on North Woolwich 76 years ago – thanks to the marvellous memory of one of the area’s oldest inhabitants, 91-year-old Joan Plant.

Locals had got used to the daily ritual of bombs attacking their neighbourhoods since the Blitz began in September, 1940. Within just a few months, hundreds of local people had lost their lives. Thousands of children had been evacuated to various parts of Britain from East London.

These included Joan and her sister Sheila, who had been sent away to Bath. Like many, they were missing their home terribly and kept in touch by letter. “We’d been told not to tell everyone where we came from, and instead say we lived a short distance from Greenwich!” said Joan.

We’d been told not to tell everyone where we came from, and instead say we lived a short distance from Greenwich!

Joan Plant

Her parents Fred and Flo were still living in their home in Grenadier Street, North Woolwich. Next door, Grandad Grey, as he was known, lived with his daughter and her three children.

Bombs and rockets and planes flying over were something families had become familiar with. Then suddenly there was a new threat: parachute bombs. These were naval mines dropped from an aircraft by parachute. They were mostly used in war by the Luftwaffe and frequently dropped on land targets.

When detonated at roof level, rather than on impact, the aerodynamic effects of their blast were maximised. Instead of the shock waves from the explosion being cushioned by surrounding buildings, they could reach a wider area, with the potential to destroy a whole street of houses in a 110-yard radius, and windows being blown in up to a mile away.

It was in March 1941 that the latest parachute bombs were dropped on homes near the Royal Docks. An air raid siren had alerted the Plant and the Grey families to go quickly to the air raid shelter in Albert Road, around two streets from their house. But the two men in each house would not be budged.

My dad and Grandad Grey said Hitler was not going to get them out of their beds.

“My dad and Grandad Grey said Hitler was not going to get them out of their beds,” said Joan, who was 15 at the time. “All of a sudden, a parachute mine sent to cause devastation hit the roof of number 13 next door to us [Grandad Grey’s house]. Everyone waited, expecting the worst, but it never happened. The whole street could have gone up, but an eerie silence was all that happened.”

“Mum and Dad and Grandad Grey told me how the bomb landed, making a kind of slithering noise,” said Joan. “Grandad Grey got out of his bed and looked up in amazement. He struggled to get out of the room and around the huge mass of green silk which was the parachute attached to the bomb – and the bomb itself. It had gone right through the roof and was hanging, hovering above the top of the stairs, but incredibly had not gone off.”

The Air Raid Precaution Wardens were on the scene of the drama within minutes and immediately starting evacuating people who had not yet left their homes. The street was cordoned off for three days while bomb disposal experts dealt with more pressing emergencies.

Joan describes, “I got a letter from my mother telling me they were safe, but that we should stay away from the home and to wait for them to let me have further news.” Eventually the bomb disposal team came and made the device safe.

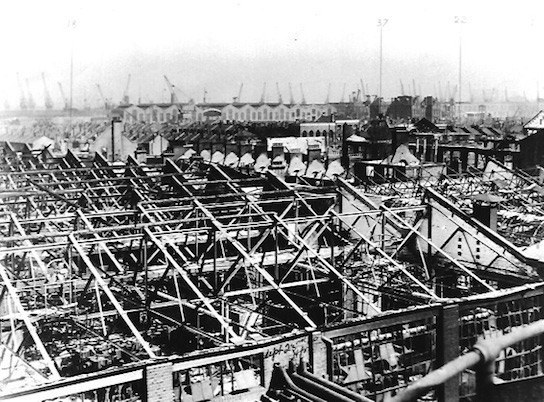

War damage

Silvertown Rubber Company, photographed in 1940. Photos: Newham Archives and Local Studies

People were allowed to return to their homes, but the remains of the mine bomb and the green silk parachute stayed – and the story of the amazing escape for families in Grenadier Street was about to take another twist.

“One morning someone asked to come inside and have a look at the bomb and the silk,” said Joan. “The silk was beautiful and everyone wanted a piece, but we were told we could not have it. As more people came to see what had become a tourist attraction, Grandad Grey put a chair outside the front door and a collecting bowl to help the war effort.

“Most people were so poor, they could only afford to donate ha’pennies or pennies. So it was amazing that more than £14 was collected by people visiting. The incredible escape had become a big story for local people.”

After a few more days the bomb and the parachute were eventually removed. The money – which equates to nearly £900 today – was then taken to the local council and went towards constructing the North Woolwich Spitfire.

No pictures exist of the parachute bomb incident. “Everything had to be kept secret during the war. And we couldn’t afford a camera anyway!” added Joan. However, after searching through the documents of Newham Archives in Stratford, I managed to track down the exact day and time that the parachute mine fell on Grenadier Street, March 20 at 1.55am.

The front page of the Stratford Express that week made reference to the fact that the overnight bombing of March 19 and 20 has been the worst so far in the history of the war to that point. But no mention was made of the miracle of North Woolwich in that edition or in subsequent editions and it seems that the story was forgotten.

Unexploded bombs remind us of the heroism shown not only by servicemen and women in combat, but also at home by the emergency services and the volunteer wardens.

Colin Grainger

The falling bombs became a way of life. Joan said, “One of the severe bombings, one evening, saw many ships hit and burning fuel escaped into the water and set it alight. Many buildings were also hit by the bombs, houses and factories.

“Of the 17 large factories which stretched in a long line through North Woolwich and Silvertown, 16 were hit. Products from many of the factories – treacle, rubber, chocolate and syrup – all began to run burning across the Albert Road, parts of which cracked open and then sealed shut again.”

Thousands lost their lives and for many years after the war, unexploded bombs were found, disrupting local life. Even 50 years on from the war in the 1970s another unexpected guest was unearthed in Plaistow. It is said to be one of biggest and hundreds of people had to be moved out while the Army blew it up. More continue to be found to this day.

I played on many bomb sites in North Woolwich and Silvertown from the late 1950s to the late 60s and I have covered many stories about unexploded bombs in my years as a journalist.

They serve as a stark reminder of what our parents and grandparents went through. They also remind us of the heroism shown not only by servicemen and women in combat, but also at home by the emergency services and the volunteer wardens. But it is the tale of the uninvited guest who came to stay in North Woolwich that throws the focus on how lives were changed forever.